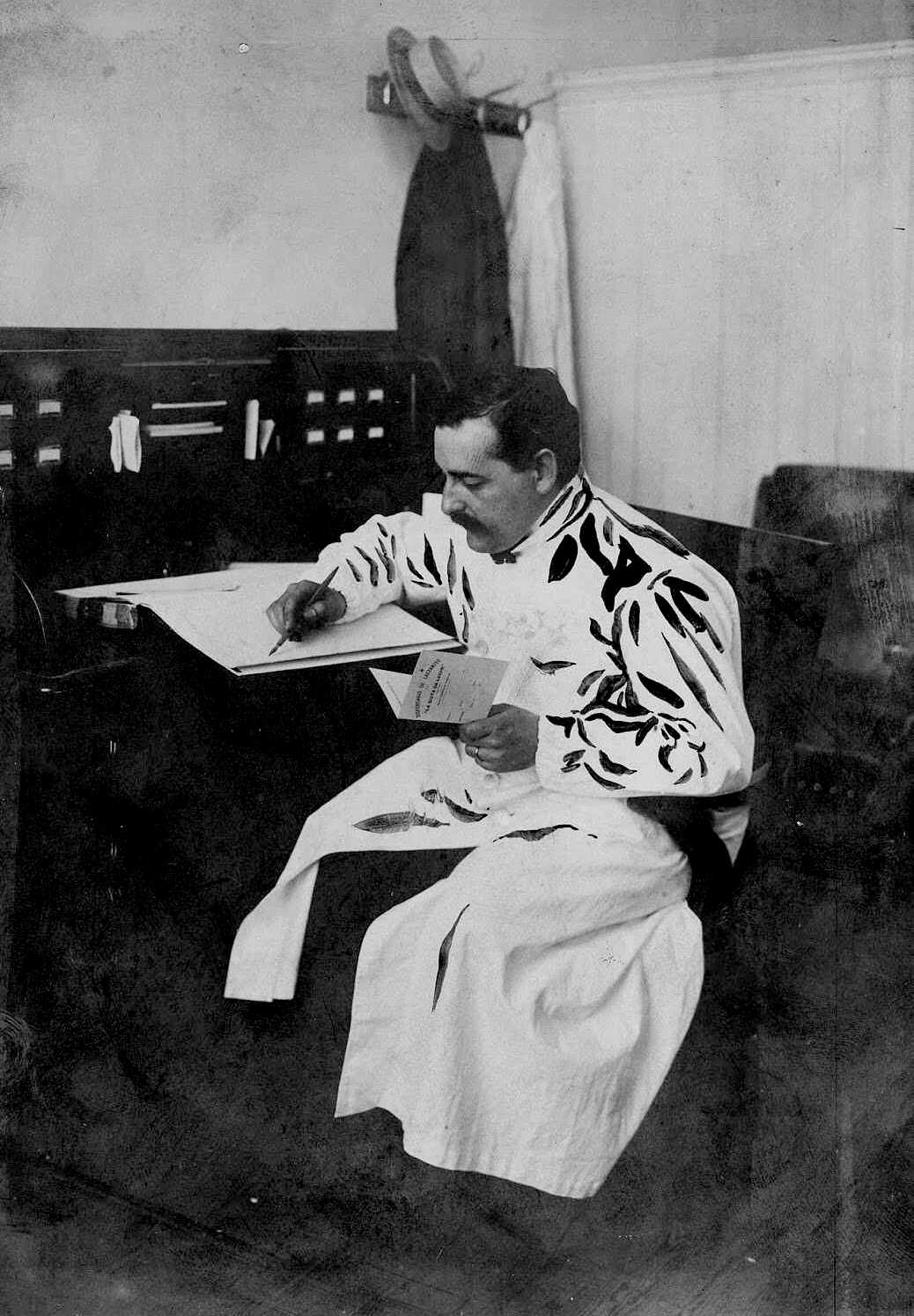

Dr. Enrique Foster

Enrique Vicente Foster (Buenos Aires, Argentina; June 19, 1878 - Buenos Aires, Argentina; c. 1939) was an Argentine university professor and pediatrician, recognized for founding in 1904 and implementing the First Children's Dispensary in the Argentine Republic to improve the situation and way of life of children whose mothers, either due to their occupations or due to the lack of milk, could not feed them in accordance with the precepts indicated by hygiene and the needs of children. [1]

Family

Enrique Vicente Foster was the son of Adelaida Ponsati Vidal (1847-1916), originally from Buenos Aires, and Enrique Foster (1842-1916), Argentine colonizer and surveyor, founder of Monte Oscuridad and co-founder of the city of Resistencia, Province of Chaco, Argentina.

His father Enrique had a natural son around 1865 with Isabel Llames (1845-?): Enrique Arturo Foster (1865-?), but a few years later he married Adelaida Ponsati, on January 17, 1873 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and with whom he had 7 other children: Alejandro Foster (1877-1951), Ricardo Ignacio Foster (1881-c.1959), María Foster (1873-1873), Celia Cecilia Foster (c.1889-?), Ricardo Luis Foster (1874-1874), Enrique V. Foster (1878-c.1939) and Carlos Foster (c.1866-?).

Alejandro Foster (1877-1951) was an agronomist, founder in 1924 and president of the Sociedad Rural Argentina de Trenque Lauquen in 1933, 1934 and 1935, and he married María Magdalena Paula Nazar Miguens (c.1864-?).

Ricardo I. Foster (1881-c.1959) married Ana Mooney, and was an Argentine lawyer and politician, deputy of the province of Santa Fe in 1934-1935, and Minister of Public Instruction of the same province from 1935 to 1937.

Celia Cecilia Foster married Álvaro Francisco Leguizamón Ovalle (1883-1956), in turn son of Guillermo Leguizamón del Llano (1853-1922), politician and one of the founders and main architects of the formation of the Radical Civic Union with whom he maintained a close relationship with Leandro N. Alem (1841-1896) and Bernardo de Irigoyen (1822-1906) until the end of their days.

The two remaining children, Maria Foster (1873-1873) and Ricardo Luis Foster (1874-1874) died at birth.

It should be noted that the son of his father Enrique's first marriage, Enrique A. Foster (1865-?), was a prosperous merchant who married the Spanish María Dolores Castaño (c.1870-?) in 1890.

Enrique Vicente Foster married Josefina Corina Tezanos Pinto Torres Agüero (1879-1979) in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on May 2, 1903, and together they had 7 children: David Foster de Tezanos Pinto (c.1900-1995), Raúl Foster de Tezanos Pinto (1910-2000), Cora Foster de Tezanos Pinto (1912-2004), Ricardo Foster de Tezanos Pinto (1916-2006), Marcelo Foster de Tezanos Pinto (1918-2007), Enrique Alejandro Foster de Tezanos Pinto and Corina Foster de Tezanos Pinto.

Josefina Corina Tezanos Pinto Torres Agüero (1879-1979) was the daughter of David de Tezanos Pinto (1849-1934), a Chilean lawyer and university professor who excelled in both the public and private spheres, and was considered an eminence in matter of law.

Biography

Enrique Vicente Foster was born on June 19, 1878 in Buenos Aires, Argentina and was baptized on September 16 of the same year. [6] His parents had settled in that city for a time, and after the signing of the Peace and Trade Agreement between the Argentine Confederation and the State of Buenos Aires in 1854, they returned to the Province of Santa Fe, Argentina. [7]

He had a prosperous career after receiving a Doctor of Medicine degree and graduated in 1902 from the city where he was born. [2]

Enrique Foster was a former practitioner of the Public Assistance Hygiene Inspectorate in 1898 and a former junior practitioner of the Central Office of Public Assistance in 1899. He was also a junior and senior at the San Luis Gonzaga Children's Hospital, the first hospital in Latin America specialized in pediatrics, in 1899, 1900, 1901 and 1902. [3]

El Niño: Thesis presented in Buenos Aires, Argentine Republic

In 1902, Dr. Enrique Foster presented a paper to apply for the title of Doctor of Medical Sciences where he shared a series of advice and opinions based on the development of the child in order to realize the evils that must be remedied in childhood. [4]

Based on his experience as Director of the Children's Hospital, Dr. Foster had observed the large number of small defenseless, undermined by the large number of diseases that devour them and to which their weak stocks tremble and bend.

"Mothers in tears who carried their little children in their arms entered the concert of life and began to feel the effects of the many thorns found in it". [5]

In the aforementioned work, the author follows the child in the evolution of his life, from his conception in the womb, until puberty, already prepared to be an adult, after having emerged victorious in the multiple battles he will have had to fight in his childhood with the diseases proper to that stage of life. Enrique Foster referred to the great division during childhood, according to the social class that the children belonged to and the environment in which they develop.

The children of the rich and the children of the poor, the first, surrounded by all the care and requests that money can provide with the love of the mother and the second, only fueled by this love and developing in means harmful to their health , enveloped everywhere by that multitude of pathogenic beings existing in the outside environment and lurking every opportunity to produce their destructive effects. However, everyone deserves a competent and well regulated diet so that their digestive system does not suffer.The author has compared the newborn child to a digestive system and nothing else, and argues that the growth, vitality, good condition of the small being, do not depend, but on the regular functioning of his digestive tract. [6] The feeding of the child will be one of the main points that Dr. Enrique Foster treats in the thesis, product of the numerous works he has done and the lessons of his teachers at the Dr. Ricardo Gutierrez Children's Hospital, the first pediatric hospital in Latin America .

Once again, the author raises the need for a doctor to have a scale by his side and systematically weigh his patients and argues:

In addition, it highlights the need in those years of nursing homes for the convalescent; where children are tuberculized in the vast majority of the harmful environment.

How many times do we not know that a child is sick just because he loses weight without presenting absolutely no other symptoms of his pathological state, until this is not declared frankly? [7]

Dr. Foster maintains the powerful influence of the nosocomial environment on poor children, admitted from a very young age to hospitals by attacking in one way or another the weak child.

In addition, it highlights the need in those years of nursing homes for the convalescent; where children are tuberculized in the vast majority of the harmful environment.

According to the municipal statistics of the year 1900, only in the City of Buenos Aires 240.79 children had died per thousand deaths, between 0 and 1 year, and in 1901, 207.56 per thousand and the author emphasizes the effort of the man to try to suppress the mortality in the world to reduce as much as possible, the sufferings of humanity. [8]

Narrate to Heal

The health of the child population had become a focus of interest in a context of dissemination of concerns about the quality of the future population of the Argentine Nation.

A series of discussions about infant mortality arose at the beginning of the 20th century and these debates included the question of whether those figures in Argentina were high or negligible. [9]

However, there was still no solid consensus on what to consider as an infant in statistical terms but in 1909, Dr. Enrique Foster, Doctor of the Children's Hospital and Official of the Health Administration and Public Assistance (Ministry of Health of the Argentine Republic) published in the Annals of this institution a study that sought to resolve this controversy, disallowing the arguments of those who were wrong in the way of dealing with statistics and took only the first year of life for the calculation of infant mortality. [10] The first National Congress of Medicine of 1916 supported him, establishing as a uniform criterion the period of zero to two years [11] and for his part, in the studies of the National Department of Hygiene, Adela Zauchinger held a broad criterion of childhood that arrived until puberty and identified in this social group people from zero to 15 years; in general terms, with the legalistic concept maintained by the dome of the National Department of Hygiene that recognized the limit of childhood as determined by Argentine civil law (12 years for women, 14 for men). [12]

Academic & Associative Processes at the Beginning of the 20th Century according to Dr. Foster

As part of an intense process of medicalization of life in general and of childhood in particular, in Argentina in the late nineteenth century, as in other Latin American countries, new medical specialties that define new objects of study and intervention. [13]

The fight against infant mortality, linked to the particular place that happens to occupy childhood, occurs together with the beginnings of the constitution of pediatrics as a medical specialty. [14]

Following especially the French and German pediatric schools, this process occurs more or less simultaneously in the different countries of Latin America.Latin American doctors travel frequently to France and Germany to visit and train in the child care services of their hospitals, in addition to studying with medical literature from those countries and towards the end of the 1920s, as part of the circulation of knowledge Scientist of the time, the reference to doctors of the United States is added.

The need to reduce infant mortality and the diseases that cause it is not the only concern that childhood raises at the time.

In Buenos Aires, abandonment, begging, street work and child crime are being cut, defined, explained as "problems" within the framework of a series of socially constructed representations of childhood characteristics; representations by which the way in which subjects must go through this stage is established and their "normal" physical behaviors and characteristics are defined. [15]

In line with the delimitation of the child as an object of study and treatment, pediatrics is institutionalized as a medical specialty and pediatricians begin to become a professional group.In 1905, as part of these institutional transformations, the Pedro de Elizalde Hospital, belonging to the Society of Beneficence of Buenos Aires, was transformed into a Hospital de Niños Expósito.It should be clarified that pediatrics is affirmed at a time when the State advances in the creation, organization and supervision of a health care system, but philanthropic institutions such as the Charitable Society still own and manage a large part of the establishments destined to such an end. [16]

In addition to child care services in hospitals in the city of Buenos Aires, among the establishments whose creation promotes the assistance to children can be mentioned the "Gotas de Leche" [17] and those founded after the creation, in 1908 , of the Directorate of Early Childhood of Public Assistance in Buenos Aires: [18] Infant dispensaries, childcare institutes [19] and nursery inspection offices. [20]

Conceived as both assistance and educational fields, they focus their approach on childcare, understood as the area of child medicine specialized in child rearing, especially during "early childhood." [21]

Childcare is constituted as part of pediatrics, although with relative autonomy with respect to it. [22]

Unlike the pediatric clinic, it is oriented towards the day-to-day care of the healthy child through the transmission to mothers of parenting methods considered rational and scientific, ensuring that the medical science guide takes the place previously occupied in the upbringing of the child on the advice of popular curators and family women. These knowledge, habitual sources of knowledge about child rearing, become strongly unauthorized by pediatricians in terms of "ignorance" and "prejudice." [23]

The intervention and persuasion strategy put into play to combat them is pedagogical and preventive.

To this end, different actions are taken, ranging from the publication of booklets, brochures and manuals for child rearing to home visits and the periodic monitoring of the child in the establishments of the Directorate of Early Childhood. [24]

These actions can be considered as part of a thorough work, never completely completed, to implement a belief in the value of children's health and in the objective and rational capacity of science to ensure it. [25]

Although balancing the results of this process would require the performance of other work, some elements that arise from statistical data can be pointed out, from the periodic reports prepared by the physicians in charge of the aforementioned care establishments. [26]

Lactation Clinic in Argentina by the French Initiative

The creation of the Puericultura Society in the City of Buenos Aires reveals the changes that affected the Argentine society of the first half of the 20th century.

The medical knowledge, in permanent boiling from the incorporation of new discoveries, particularly those resulting from the bacterial revolution, caused a wide range of transformations. In this way, ideas about the role of medicine in society as well as the role of medical professionals were modified; This process gradually moved to practices and generated a series of developments in existing public health institutions. [27]

Childcare, constituted as a scientific specialty in medicine, sought the integral protection of the mother and the child from the combination of two ideas: the conception of health as an integral value and the responsibility of the State in achieving this objective. The Directorate for the Protection of Early Childhood was created within the Public Assistance of the Municipality of Buenos Aires, in 1908, from the reception in the country of the guidelines of childcare, a new medical specialty originated in France.

Dr. Enrique Foster organized the First Gota de Leche in 1904, in which he followed the model of the institutions of the French farmers. This initiative received a municipal subsidy and consequently a close link was built between that agency and the municipality. [28] Thus, municipal health institutions received and adapted the ideas of childcare at the request of a group of doctors.Its first directors, Dr. Foster (1908-1912), Dr. Silvestre Oliva (1912-1927), Dr. Mario H. Bortagaray (1927-1946) and Dr. Hernando Magliano, generated a service for care integral of infants within the municipal health agency. [29] By 1934, their services assisted more than half of the children under five years of age who lived in the city of Buenos Aires, through twenty dispensaries and five Puericultura institutes.

Child Protection & Consolidation of Pediatrics

During the second half of the 19th century, infant mortality in the City of Buenos Aires was very high, but its reduction was that drastic, according to a statistical chart made by the Argentine doctor, Dr. Gregorio Aráoz Alfaro in 1927 where it shows how it descended from more than 190% in 1886 to 85% in 1926.

As it has been established by other authors, this sustained decrease in infant mortality in the period from 1875 to the first decade of the 20th century was due to the construction of public works for health and improvements in medical care.

Meanwhile, pediatrics was increasingly asserting itself on a scientific basis, whose two columns were bacteriology and the chemistry of digestion and nutrition. [30] Simultaneously, during the last decade of the 19th century, several Early Childhood Protection initiatives followed in France: Pierre Budin's nursing offices, Variot's Dispensary in Belleville and Léon Dufour's Drop of Milk in a village in Normandy , to distribute pasteurized milk and educate mothers.

This system was reproduced in the Argentine Republic and in 1904, Gota de Leche paths were installed in the Province of Córdoba and Buenos Aires.

In Buenos Aires, Enrique Foster opened his Gota de Leche and in 1904 this movement prospered. [31] In 1908, the Child Protection Section in Public Assistance was created, and three years later the Early Childhood Protection Ordinance was passed.

The monthly assistance to the infant kitchen of the seven dispensaries and five childcare institutes was approximately 30,000 visits for the first half of 1917.

In 1926 the system came to have 18 dispensaries for infants in addition to the five institutes, in which there was hospitalization of the mother with the newborn child. [32]

The high mortality rates of the period, malnutrition, child labor and alarming numbers of child abandonment demanded answers and it is against this background that the Puericultura (study and practice of health during the first years of life) has been established in the Argentinian republic.

Organization for Early Childhood Protection Services

Public Assistance in Buenos Aires through the Early Childhood Protection Section provides preventive assistance to infants from birth to 2 years of age.

He began his duties on January 1, 1908, formalizing the First Infant Dispensary which, under the name of the office Gota de Leche, he had founded 4 years earlier in 1904, Dr. Enrique Foster. [33]

Gradually and as the functions required it, it expanded its number until it reached the current organization, which has 20 dispensaries for infants, 5 Institutes of Childcare and the Nodrizas Inspection Office.

The dispensaries of infants distributed in all the neighborhoods of the City of Buenos Aires, have an office, directed by a specialist doctor of Childcare and Pediatrics.

The Puericultura Institutes have, in addition to the office for local infants with comfort to hospitalize infants, whether healthy or sick, with conditions usually derived from improper feeding, together with the mothers.

Mothers take their children for the doctor to teach them to direct the raising of their child, trying to make breast milk the basis of their child's diet, and in the event that it is insufficient or unable to do so, provide the child with Artificial food appropriate to their age.

To this end, annexed to each dispensary works the milk kitchen, where all the nutritional formulas that the doctor needs to use not only in the diet of the child but of the sick child are prepared. [34]

The Drop of Milk

As a result of the propaganda carried out, it has been possible to put into practice the Installation of a Infant Dispensary, an establishment whose purposes, through the cooperation of the authorities and the public, must be fully fulfilled, improving the situation and the gender of life of the children whose mothers could not feed them in the manner and in accordance with the precepts indicated by the hygiene and needs of Children. [35]

The First Dispensary has been established in the premises of street Cerrito 892 in Buenos Aires, under the direction of Dr. Enrique Foster, who after a thorough study of the needs that this kind of institutions should fill, required modern, simplified machinery that they ensured the most complete purification of milk, placing it in unsurpassed conditions of hygiene and feeding. [36]

Dr. Foster's office had an attached tambo in the City of San Vicente (Province of Buenos Aires), where the milk, just milked, was subjected to pasteurization operations and placed in sterilized bottles. [37]

Death

Enrique Vicente Foster died around 1939 in Buenos Aires, Argentine Republic after an extensive professional career, and his remains rest in the same city.

His studies, framed in the good development of early childhood, left as a legacy a complete collection of texts that continue to be studied over the years.

References

- ↑ La Pediatría como Disciplina Cultural y Social - Pediatrics as Cultural and Social Discipline. Dr. Miguel de Asúa.

- ↑ EL NIÑO, Thesis presented to qualify for the degree of Dr. in Medicine Buenos Aires, Argentina 1902.

- ↑ Thesis presented to qualify for the Doctor of Medicine degree. 1902. No. 1291. Page 3.

- ↑ El Niño.Tezanos Pinto, Jacob. Buenos Aires, 1902. Printing and Publishing House of Agustín Etchepareborda, Page 17.

- ↑ El Niño.Tezanos Pinto, Jacob. Buenos Aires, 1902. Printing and Publishing House of Agustín Etchepareborda, Page 18.

- ↑ El Niño.Tezanos Pinto, Jacob. Buenos Aires, 1902. Printing and Publishing House of Agustín Etchepareborda, Page 19-21.

- ↑ El Niño. Buenos Aires, 1902. Page 21.

- ↑ General Directorate of Municipal Statistics of the City of Buenos Aires (DGEM), 1900-1910.

- ↑ EPIDEMIOLOGY. Medical Week, Buenos Aires, v.25, n.20, p.552-555. 1918.

- ↑ Dr. Foster justified the extent of the repercussions achieved by the subject as follows: ↵ "Early childhood mortality is one of the most interesting topics because of the number of problems involved, both hygienic and sociological; no It is surprising, therefore, that it is often treated both by scientific journals and by the daily press, of which we must congratulate ourselves, since it is indispensable to facilitate the task of those who are in charge of studying this mortality, to seek its causes and try to combat them "(Foster, 1909, p.208).

- ↑ Counting to Cure: Statistics and the Medical Community in Argentina, 1880-1940.

- ↑ The classification system used by Dr. Zauchinger was as follows: 0 to 7 days, 7 to 30 days, 1 to 2 months, 2 to 3 months, 3 to 6 months, 6 to 12 months, 1 to 2 years, 2 to 6 years, 6 to 10 years, 10 to 15 years (Argentina, 1913). ↵ It's interesting to note that its statistical classification prioritized the stage of early childhood as it segmented into a greater number of categories (seven) those under two years of age, integrating the rest of the child population into only three categories that involved time intervals longer.

- ↑ ARMUS, Diego (Comp.). Avatares de la medicalización en América Latina, 1870-1970 .Buenos Aires: Editorial Place. 2005.

- ↑ Badinter, Elisabeth records that the names "Pediatrics" and "Childcare" adopted by the new specialty appear for the first time in France in 1872 and 1864, respectively.

- ↑ Bourdieu, Pierre. Sociología y Cultura. México: Grijalbo. 1990.

- ↑ The Sociedad de Beneficencia, created in 1823 during the Government of Rivadavia to organize a large part of education and social assistance in general, has lost much of its power and initial responsibilities for the time here, but continues to run several hospitals in the city of Buenos Aires. He always maintained an ambiguous relationship with the State; ambiguity derived from its character as a private entity created and financed mostly by the State to perform public functions.

- ↑ Initiated in 1904, replicating those in France, they provide milk. They start as a private initiative and then receive municipal funding.

- ↑ This institutional development aimed at children cannot be generalized for the entire Argentine territory, since in the interior of the country, just entering the 1930s, centralized national policies are assigned to the National Department of Hygiene.

- ↑ BILLOROU, María José. Maternal and child protection must be placed in the foreground in a country like ours: childhood protection policies in Argentina in the early twentieth century. Paper presented at the Conference "History of Children in Argentina, 1880-1960" Los Polvorines: National University of General Sarmiento. 2008.

- ↑ Located in poor neighborhoods of the city, infant dispensaries prepare and deliver food and are also outpatient clinics for newborns where "educational assistance" is made to mothers. In the childcare institutes the medical follow-up of the newborn is done and there are hospitalization rooms. The Nodrizas Inspection Office controls the health conditions of the milk of women employed as nurses, as well as the food and care that their own children receive.

- ↑ This institutional development aimed at children cannot be generalized for the entire Argentine territory, since in the interior of the country, just entering the 1930s, centralized national policies are assigned to the National Department of Hygiene.

- ↑ The disciplinary delimitation and the relationship between the two are not clearly or uniformly defined at the time studied. For some authors of the time, childcare is a part of pediatrics; for others, both approaches to childhood constitute disciplines with equal rank within medicine, making it impossible to project the current criteria of distinction between specialties towards the time studied.

- ↑ FOSTER, Enrique. Report on the operation of the infant dispensary "La Gota de Leche". Latin American Archives of Pediatrics, year 3, n.3, p.104-110. 1907.

- ↑ BOLTANSKI, Luc. Prime éducation et morale de classe . Paris: Mouton. 1969.

- ↑ FOSTER, Enrique. Memory on the operation of the "Drop of Milk". Latin American Archives of Pediatrics, year 2, n.7, p.275-281. 1906.

- ↑ FOSTER, Enrique. Protection and assistance of children: Report submitted to the Directorate of Public Assistance and corresponding to the year 1910. Latin American Archives of Pediatrics, year 1, t.5, n.1, p.122-139. 1911.

- ↑ Biblioteca Universidad Nacional de La Pampa. Pág 3.

- ↑ Puericultura Society of Buenos Aires, Chapter 1. Page 14. UNLPAM Library. Retrieved on October 9, 2019.

- ↑ Library of the National University of La Pampa. The Puericultura Society of Buenos Aires. Chapter 1, page 14. Accessed October 9, 2019.

- ↑ La Pediatría como Disciplina Cultural y Social/Pediatrics as cultural and social discipline. Dr. Asúa. Pág 232-236.

- ↑ Argentine Archive of Pediatrics, 2012; 110 (3). Page 231-236.

- ↑ Eighth Pan American Child Congress, Washington, D. C., May 2-9, 1942. Pág 315. Consulted by Ezequiel Foster.

- ↑ Eighth Pan American Child Congress, Washington, D.C., May 2-9, 1942. Pág 315. Consulted by Ezequiel Foster.

- ↑ Biblioteca de Ciencias Económicas y Estadísticas of the National University of Rosario, Argentine History between 1860 and 1950.

- ↑ Caras y Caretas Magazine. Year 1905, page 8 (335).

- ↑ Spragzutti, María Inés. Monday, April 1, 2013. Consulted by Ezequiel Foster on October 9, 2019.