Richard Foster (c.1648-1730) / Cloth-worker

Richard Foster (Ossett, West Yorkshire, England, UK; c. 1648 - Ossett, West Yorkshire, England, UK; September 17, 1730) was an English dissident and cloth maker who built Hassell Hall in the late 17th century .

Family

Richard Foster was the son of Dame Foster (1614-2 February 1709) and Richard Foster (1623-20 September 1710), both of Ossett. His parents married around 1648, and together they had at least one child.

Richard Foster married Hannah Burnet Jackson (1658-1724) on January 23, 1687 in Bilston and together they had 7 children: Stephen Foster of London (1682-1719), Joseph Foster of Ossett (1693-?), Richard Foster of Flanshaw Lane (1686-1729), Hannah Foster (1674-1763), Benjamin Foster of New York (1695-1735), Elizabeth Foster (c.1685-1740) and Mary Foster (1693-1760).

One of her sons, Benjamin Foster (1695-1735), emigrated to the United States of America around 1718 and for a time was a tanner and administrator on the estate of his mother-in-law, Jannetie Mesier (1671-1728). He then married Johannah Van Imbroch (1699-1748), descendant of the Dutch, and great-great-granddaughter of Jessé de Forest (1576-1624), a prominent explorer, leader of a group of Walloon Huguenots who fled Europe due to religious persecution, and emigrated to the New World, where he planned to found New-Amsterdam, which is now New York City.

Richard Foster (1686-1729) of Flanshaw Lane, married Mary Lumb (1695-1757), of a prominent Wakefield family, and died around 3 a.m February 1, 1729.

Another of his daughters, Hannah Foster (1674-1763), was born in Ossett and moved to London. She then married the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743), a nonconformist British minister, successor to Oliver Heywood (1630-1702) from 1702 to 1743 inclusive.

Mary Foster (1693-1760), married Reverend Samuel Hanson (1693-1763) de Wyke, cousin of John Hanson (1715-1783), the first president of the Continental Congress of the United States during the period of the American Revolution. They were both the grandparents of Colonel Joseph Hanson (1774-1811), who gained so much notoriety when large gatherings of Manchester weavers were held in 1808.

It should be noted that Richard's wife, Hannah Burnet Jackson, was the daughter of Cristopher Burnett (1630-?) of West Yorkshire, and Gertrude Jackson (1631-1695). His maternal uncle, Peter Jackson of Leeds, was in arms for the king against Parliament, and was deputy bailiff to Robert Hurst, the eldest, of Leeds, in 1655.

Hannah died on October 4, 1724 around 5 p.m and was buried 3 days later in the old Bunhill Fields cemetery in central London.

Biography

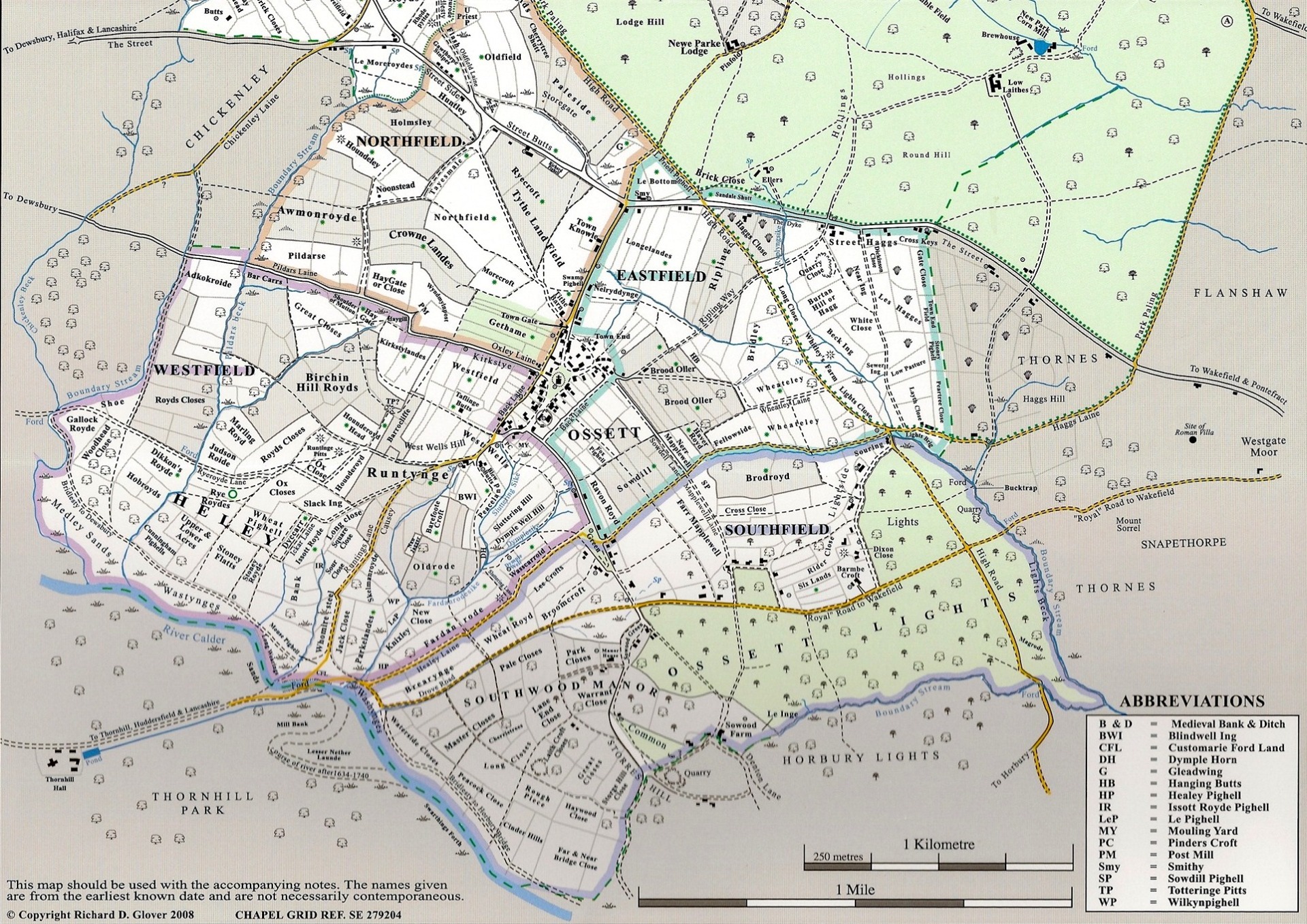

Richard Foster was born in Ossett, Yorkshire and lived for a long time in Ossett Lights, in the Haggs Hill area, where his family owned land and property.

Around these years, it was a time of great change, including the dissolution of monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII (1491-1547), which greatly reduced the influence of the church and the power base of wealth and privilege monasteries, the bubonic plague that killed many people in Wakefield in 1625, another plague outbreak in 1645, the English Revolution (1642-1651) with the execution of Charles I (1600-1649) in 1649, and a 4 month flu epidemic in 1675 that killed many people in the Wakefield area and was known at the time as 'Jolly Rant' or 'New Delight'.

During the revolution, Ossett was close to the events with the battles at Wakefield, Seacroft, Bradford, Selby, Tadcaster and near Wetherby, with strong support for the parliamentarians of statesman Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), in the Yorkshire villages. These events must have affected the residents of Ossett, who made their living making woolen fabrics with looms in their homes.

Richard Foster produced woolen cloth and, together with his wife, they sheared sheep, combed the wool or carded it to straighten the fibers, and then spun them into yarn with a spindle and wove them into cloth on a simple loom.

In 1650, the wage including food for a weaver was 3 denarii per day and only 1 denarius per day for spinning. If the wool spinner provided his own food, the salary was 4 denarii a day. Manufacturers then took their finished fabrics to the Wakefield market, where they were bought by middlemen to be sold at a profit in places like London or Cambridge.

'The residents of Ossett, a village three miles from Wakefield, have been employed in making broad wool fabrics since time immemorial. In this year, weavers and employees of that trade had to work 15 hours a day for eight pence. The horn was honked at five in the morning, starting time, and also at eight at night, time for leaving work.'

Some documents indicate that Richard Foster was also an independent dissident, at a time when there was much persecution and it was dangerous not to conform to the official Protestant religion and great efforts were made to trap those of a different opinion.

In a letter written by his son-in-law, the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743) to his granddaughter in 1731 refers to Foster as follows:

'He feared God from his youth and above many, he excelled many others in gifts and knowledge, and God put an honour upon him in making him eminent in grace and usefulness too. He was a solid, judicious Christian, strictly pious and devout in his duty to God, and conscientious in his dealings with men. Though he lived a considerable time and had much to do with men and business, yet he hath left a good name, a fair character, behind him.

Very careful he was to instruct his family in the things of God, keeping up religion and the worship of God constantly in his house, as well as attending diligently on public ordinances. He was an exceedingly kind and indulgent husband, a tender-hearted, affectionate father, a good master and useful neighbour, and I am persuaded he wdl be very much missed in this place, for there are few like-minded, so able and willing to lay out themselves for God.

He was a great honorer of the good men and ministers of both denominations, conformists or non-conformists, being ready at all times to support and encourage them. But now he rests from his labours, and his good works follow him, in the blessed recompence and rewards of glory.'

Excerpt from a letter writtenon March 11, 1731 by the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743) to his daughter Mary Dickenson (1717-1804) in London, England, when she was 14 years old.

Death

Richard Foster died after suffering severe strangulation pains for a considerable time, on September 17, 1730, in Ossett. He was buried a day later in the churchyard of the former Anglo-Saxon Church of St Peter and St Leonard in Horbury, West Yorkshire, England.

"Mr Richard Foster of Ossett, my dear and honored father-in-law, died on September 17 after suffering severe strangulation pains for a considerable time, and had been extremely useful as a Christian and as a merchant."

Rev. Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743) in Northowram Register.

Bibliography

- Wakefield Manor Book, 1709. YAS Record Series Vol. 101.

- Ossett, deeds and documents. Yorkshire Archaeological and Historical Society. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- 'Leeds Intelligencer', June 20, 1775.

- Memorials of Deeds (1704-1970). The Deeds Registry, West Yorkshire History Centre WF1 1JG.

- Familiae Minorum Gentium, Vol 1. Page 75.

- The Nonconformist Register of baptisms, marriages, and deaths: 1644-1702, 1702-1752 by Heywood, Oliver, 1629-1702; Dickenson, Thomas; Turner, J. Horsfall (Joseph Horsfall), b. 1845. Page 307.

- Horbury Parish Register.

This site is developed by Westcom, Ltd., and updated by Ezequiel Foster © 2019-2021.