During the 17th and early 18th centuries, the situation in Ossett, a town located in the county of West Yorkshire, England, was very different from today, as it was a semi-agricultural town of working people who made a living manufacturing fabrics in small scattered farms.

There was only one place of worship, but the authorities expected people to conform to the Church of England with its beliefs and liturgical form of service, and it was very dangerous not to conform to the official Protestant religion, and great efforts were made to catch those who they had a different opinion.

Dizzying Changes

In the late 17th century, the English church described itself as Catholic and Reformed, with the English monarch as its supreme governor.

For decades after Henry VIII's (1491-1547) reform, English dissenters opposed state interference in religious affairs and founded their own churches, educational establishments, and communities. These Protestant religious groups who dissented from the "established church" in England disagreed with submission to authority above God and fought for a far-reaching Protestant Reformation, which briefly flourished during Oliver Cromwell's (1599-1658) protectorate.

Although the lives of many Christians were in danger, there was a simultaneous effort to preserve the virtues of Christianity while many adapted to the new rationalistic and scientific thinking. Its that the dissidents or separatists felt that their defense of the kingdom of reason was directed solely and exclusively by God. It was this absolute reliance on reason that compelled these Protestant groups to distance themselves from religious controversy within the "established church."

For them, Jesus Christ was the only leader of the Church and the Scriptures were the only sufficient, sure and infallible rule of all knowledge, faith and practical obedience, thus opposing both the creeds and the offices of the Church of England.

In fact, all who held office under the Crown were required to take an oath of allegiance and supremacy, sign a declaration repudiating certain teachings, and be educated according to the established Church.

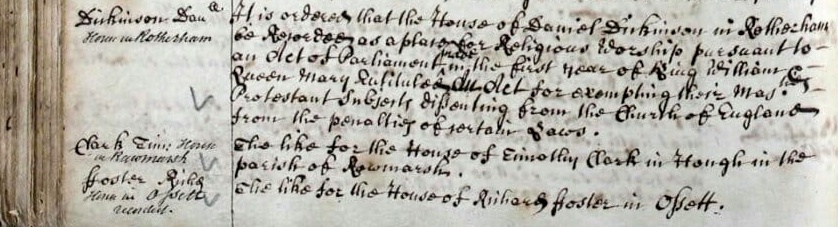

On October 4, 1683, eleven people from Ossett were tried at Wakefield for being dissenters. One of the latter, John Rider, refused to take the oath of allegiance and was fined £100 and sent to York Castle until the fine was paid. And when the laws were relaxed on May 24, 1689, two Ossett dissenters, John Bradford and John Atacke, immediately applied for permission to hold meetings in their own homes, which was granted on May 8, 1689.

Until the Toleration Act of 1689, attendance at the established church in England was compulsory, and the severity of the religious laws caused much suffering. This law allowed freedom of worship to non-conformists who had not committed themselves to the oaths of allegiance and supremacy, that is, those who did not agree, but not Roman Catholics.

Protestant groups were allowed to have their own places of worship with their own school teachers, provided they accepted certain oaths of allegiance.

Richard Foster (c.1648-1730), a cloth-worker, also later applied for permission, joining many other preachers who in 1706 were eager to welcome the faithful into their home despite recent prosecutions and imprisonments.

Dangerous Times

Its hard for us to realize how much courage and determination was required of these preachers and founding fathers at that time. These men of faith could have their own services, but nothing more. They were barred from universities and all civil and military appointments. In addition, they were required to have a license, register their meeting places, and meeting in other places was strictly prohibited. It would be more than a century before these restrictions began to be lifted.

Despite these difficulties, the West Riding of Yorkshire Quarter Sessions recorded that Richard Foster (c.1648-1730) continued to use his house as a Dissenting place of worship in the early 18th century. Furthermore, in 1717 they decided to establish a larger meeting place at Ossett and Richard Foster (c.1648-1730) set aside his tent for services and his son-in-law, the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743), a preacher from Northowram, went to deliver his first sermon, in the place most It would later be known as the Congregational Church.

They were difficult years of change, restlessness and anguish but these men took on the great task of continuing the work in Ossett by distributing printed sermons and preaching the Word of God.

In 1703, Queen Anne (1665-1714) received a delegation of these preachers who had to present their declaration of allegiance upon entering. He received them with grave impoliteness, in total silence, because his personal allegiance to the Church of England was genuine and sincere, but excessively intolerant. She later deliberately encouraged legislation that would close the academies where these ministers were trained, and another law that required all teachers to be licensed.

These harsh laws were discussed when George I of Great Britain (1660-1727) came from Hanover to claim the crown, tolerated only because it would maintain the Protestant succession and keep the Catholic Stuarts from the throne. It was no doubt convenient to grant this reprieve to dissenters, and perhaps it was this slight relief that encouraged the founding of a larger meeting place, in what was Richard Foster's (c.1648-1730) pressing shop, in 1717.

During this time was a time of great change in England, beginning with the dissolution of the monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII (1491-1547), which greatly reduced the influence of the church, the bubonic plague which killed many people in Wakefield in 1625, another outbreak of plague in 1645, the English Revolution (1642-1651) with the execution of Charles I (1600-1649) in 1649, and a 4-month-long influenza epidemic in 1675 that killed many people in the Wakefield area and was known at the time as 'Jolly Rant ' or 'New Delight'. However, through the lives of these preachers, the Word of God continued to reach the inhabitants of many towns and each of them responded to God's call knowing that their reward would not come until the next life in eternity.

A valuablely preserved document passed down from generation to generation, written by the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743) to his daughter on March 11, 1731, refers to the character of Richard Foster, and his unwavering faith in God despite adversity and even shortly before of his death by strangulation in 1730.

"My dear child, in answer to your sincere and repeated request, I have at last taken time from my other necessary and urgent activities to transcribe the sermon which I preached at Ossett on the 18th of September, 1730, being the day on which my dear and honored father-in-law, your good grandfather, was taken to the grave, having finished his career in this world, at 78 years of age."

"The children and grandchildren can and should consider it a great and valuable blessing to be the posterity of those men who, fearing God, occupied their time and place in the world with good purposes and were useful to their generation, who have given them a good example in all aspects and evangelical duties, have given them many pious and solicitous instructions, and have raised to God many innocent and fervent prayers for them."

Another carefully preserved document describes in more detail the personality of Richard Foster (c.1648-1730), as well as his dedication and commitment to God in those years.

"He feared God from his youth. He was a sound and judicious Christian, strictly pious and devout in his duty to God, and conscientious in his dealings with men.

He took great care to instruct his family in the things of God, constantly maintaining the faith and worship of God in his house, as well as diligently attending to public ordinances.

He was a very kind and understanding husband, a loving and tender father, a good leader and a helpful neighbor, and I am sure he will be greatly missed in this place, as there are few with such ideas, so capable and willing to help and give of themselves to God."

"Great motivator of good men and ministers of both denominations, conformists or nonconformists, being willing at all times to support and encourage them. But now he rests from his works, and his good works follow him, in blessed reward and glorious rewards."

Extract from a letter written on March 11, 1731 by the Reverend Thomas Dickenson (1669-1743) (Son-in-law of Richard Foster) to his daughter Mary Dickenson (1717-1804) (Granddaughter of Richard Foster) in London, England, when she was 14 years old.

This website is developed by Westcom, Ltd., and updated by Ezequiel Foster © 2019-2022.